Thinking about using single-blind peer review for your next conference? Here’s the low-down.

Peer review has been a foundation of the scientific method since the 1600s. And, despite its flaws, it’s still the best option out there for validating scientific and technical research.

There are three common forms of reviewing: single-blind peer review, double-blind peer review, and open review. When you’re planning your conference’s review process, it’s a good idea to have an understanding of the benefits and drawbacks of each before you commit to one method.

I’ll be covering single-blind peer review in this post. But you should read up on double-blind and open review too.

Definition of single-blind peer review

Single-blind peer review is the traditional method of review. In it, reviewers know the identity of authors, but authors don’t know the identity of reviewers. (In double-blind review, neither reviewers nor authors know who the other party is. And in open peer review, authors and reviewers are both visible to each other. ) If you’re planning to use a robust conference management system, it’ll let you hide reviewers identities easily and allow them to leave anonymous comments for authors.

Like any other form of peer review, there are advantages and disadvantages to single-blind.

Advantages of single-blind review

Keeping your reviewers anonymous allows them to critique work without being influenced by your authors. Authors can’t contact the reviewer since they don’t know who they are. This takes a considerable amount of pressure off your reviewers and allows them to judge research more objectively. And, because they know who the author is, they can use their knowledge of the author’s previous research to aid in their assessment.

The best peer review is honest and unflinching. And sometimes, this means shining a bright light on a work’s limitations so all can see them. But most people don’t want to put themselves in the firing line. Single-blind peer review eliminates this as a problem and enables the reviewer to be more honest without fear of public criticism.

Disadvantages of single-blind review

A study carried out by the Publishing Research Consortium found that researchers rate the effectiveness of single-blind significantly below double-blind peer review. While single-blind peer review was the most predominant form of reviewing identified in the study (with 85% of respondents claiming to have used this system), researchers preferred other methods. In fact, only 52% of researchers assessed would label single-blind reviewing as effective (whereas 71% chose double-blind). It’s worrying to think that almost half of the people who are supposed to benefit from this system have little confidence in it.

The ethics of single-blind peer review are still a topic of discussion. While reviewers are anonymous, they can see who authors are. So single-blind peer review doesn’t protect your authors against gender, racial or geographic bias. Or any sort of bias.

And reviewers may depend too heavily on an author’s or an organisation’s reputation, allowing it to blind them to the quality of the research in front of them.

Consider your review process in its entirety

Having said that, peer review at a conference is about much more than selecting a method of review. Conference reviewing usually happens over a few busy weeks, and most of your reviewers will be giving a substantial voluntary time commitment on top of an already busy workload. So, regardless of whether you’re using single-blind or not, you need to think about how you’re constructing your peer review process. A poorly-built one can create unhappy reviewers who fail to deliver quality reviews, withdraw their offers to take part, or go AWOL entirely…

To prevent this sorry state of affairs, take a few steps back when you’re designing your process and consider it in its entirety. How many submissions will you assign to each reviewer? How much time will you have between giving out assignments and sending acceptance letters? Is this a fair ask of your reviewers?

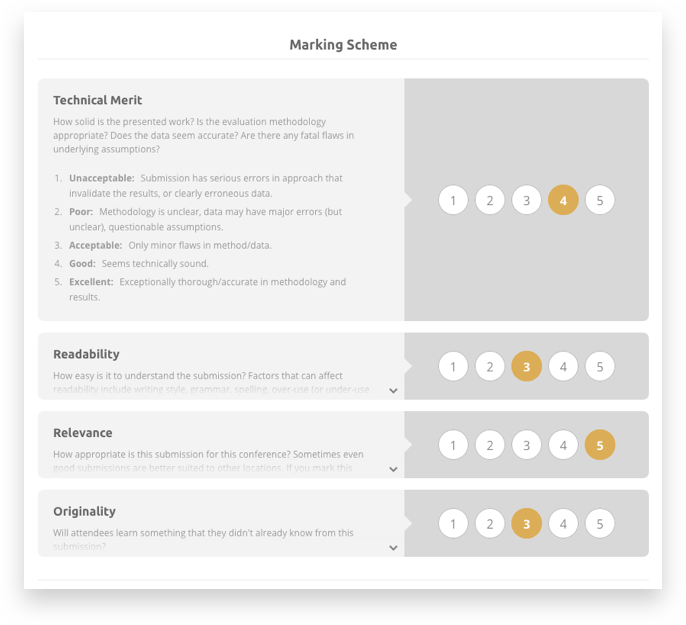

On top of this, consider how long it may take reviewers to formulate individual reviews, as well as how long it will take them to physically enter each one into your online peer review software or Google form. This second part might not be a big deal if people are reviewing one or two submissions. But if your reviewers are working through a long list of papers, any time they spend recording their reviews is time they may not give to completing more of them.

An example of one-click reviewing on Ex Ordo

5. Tips for creating a reviewer-friendly process

1. Find a happy medium between detail and speed. Compare the minimum info you need before fairly accepting (or rejecting) a submission, to the ideal, highly-detailed review. Play around with your marking scheme until you find the configuration that will give the best results in a realistic amount of time.

2. Eliminate optional sections. And make sure you’re following online form best practice. For example, if you have lots of optional sections for reviewers to complete, ask yourself whether these sections are truly necessary, and if they’re not, consider scrapping them.

3. Don’t overload reviewers. Make sure you’ve got peer review software (or an offline allocation process) that will manage how many submissions are assigned to each reviewer. Any worthwhile peer review system will allow you to set the max number of submissions that each reviewer should be allocated, but if you’re taking your allocation offline, make sure you set a fair limit.

4. Don’t pair authors with reviewers from the same organisation. Whether you’re using single-blind, double-blind or open review, asking reviewers to critique their colleagues’ or friends’ work usually negates any blind conditions and can compromise your review system. Use your peer review software to prevent nepotism in review.

5. Select user-friendly software. If you’re asking reviewers to use peer review software that’s frustrating or confusing, you won’t get the best reviews from them. So make sure you get set up with user-friendly peer review software like Ex Ordo.

Still unsure whether single-blind is right for your event?

Like all types of review, I could make a case both for and against single-blind. A great thing about conferences is that you and your organising committee probably enjoy more freedom than the editorial board of a traditional journal when it comes to choosing your method of peer review. So if you still can’t decide, you could follow the lead of the organisers of this computer science conference. Curious about whether review conditions can reduce reviewer bias, they discovered that no experiment had been done on single-blind vs double-blind in their field. So they decided to carry one out as part of their conference review process.